December 2018–

January 2019

Equip

(Ephesians 4:12)

------------------

|

Adding Up the Numbers

By Brenda Evans

“This makes 843 sticks,” Mama Eliza, my paternal grandmother, wrote in her diary on September 17, 1934. She meant the sticks of tobacco hung up in the barn that cutting season. It mattered. She needed to know. Standing in plain sight was a long winter without her husband, my Granddaddy D. Without his oversight; without his income from hauling jobs in their beat-up old truck; without him to provide for her and their eight children.

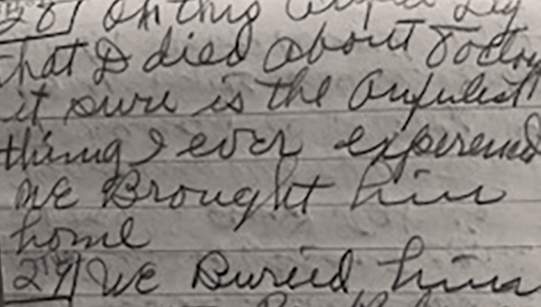

Granddaddy D died four months earlier in a freak farm accident, a hundred steps from their front door. He lost his balance climbing over a hog-wire fence. The tobacco stick he carried impaled him during the fall, and he died two days later in a Nashville hospital. Selling a jag of dark-fired tobacco over the next few months would be her main cash income without Granddaddy D.

Every part of raising dark-fired tobacco in Middle Tennessee in 1934 was labor intensive. After the leafy stalks were cut in the field, heavy four-foot sticks were hung high on the barn’s tier poles. Within a few days, firing began.

Long rows of hickory slabs were set afire on the barn’s dirt floor then smothered to a smolder with hardwood sawdust. Acrid smoke and ventilation in the barn drew out the tobacco’s moisture, leaving supple rust-colored leaves to be stripped from the stalks, tied into bundles called “hands,” bulked, and sold. If the price stayed high enough, it meant good cash for the winter months.

Granddaddy D was gone, but the work had to go on. Their son Tal, age 20, began the firing. Mama Eliza and her daughters hauled hickory slabs for him. On October 12, she wrote: This is D’s birthday he would of Been 50 if he had Lived untill today.

She bought a neighbor’s milk cow and hired a man to plow on the lower side of the road Breaking up ground to sow Oats. She and her five girls dug sweet potatoes and made green-tomato catsup. Hay was cut and brought in. Corn picked. Fires built and allowed to die down in the tobacco barn, then rebuilt. And on it went.

Over the next 40 years, Mama Eliza records her life in numbers and figures—accounts of how many, how much, who, and what. At the end of 1934, the year Granddaddy D died, she compiled a list of deaths and dates for 17 relatives and friends (including Granddaddy D), a practice she continued until her death 40 years later. She noted births, too, and eight marriages, including three of her oldest children: Guy (my father), Irene, and Lucille.

She tallied buckets of blackberries bought from neighbor children over nine July days, 15-and-a-half gallons for $2.52. She recorded pains and pleasures as well: a storm ripped the canvas off Irvin Groves’ tobacco plant bed on March 31. Two neighbors traded cars on April 1. Another came home from the U.S. Marines on April 10. “Old Jersey” birthed a calf on May 19, and the red sow had pigs on October 28.

As the years passed, her records became more detailed. In 1936, she wrote, I got white face cow from Dick [a son-in-law].” Four years later, she sold the cow’s second calf for $41.70. She kept records of debts and loans, too. Leslie [her third-born son] Let me have 16.00 at Xmas, she recorded. Later, Leslie paid for my overshoes 1.98. I owe Leslie $9.00 on hauling Ties. Below that list of debts to Leslie, she listed nine payback entries, all debts settled with her third-born son. Another June she wrote that Guy, my father and her first-born, finished shearing all the sheep and Robbed one stand of bees. We set tobacco. Up to 90. No rain.

On a summary page, she added up baby pig births: The Little spotted sow has 7 pigs. the Big spotted sow has 5 pigs. The old red sow has 11 pigs. Another notepad is devoted to measurements for her 20 or 30 sewing clients. A woman named Jeanette measured waist 30, skirt length 24, ruffle 10, waist back 15, hips 38, bust 35, sleeve from top 4. Another lists hours and payments for six workers she hired for farm and timber work, and $1.75 she paid the peddling Rawleigh man for ointments and liniments.

A red and orange notepad from Armour’s Big Crop Fertilizers has 16 pages of debts and payments and two pages of handwritten prayers for 1940. Some months she borrowed from my father, Guy; other months she lent him money—back and forth, they went. Cash was hard to get, hard to keep. Whoever had it lent it; whoever borrowed it repaid. She kept the record.

Near the middle of that notepad she wrote two prayers to pray publicly at Rock Springs FWB Church. One is for the FWB League that had recently begun:

Dear Heavenly Father we…come to this place to worship thee, and we hope for no other purpose only to serve a true and Living God….Bless this league and each and ever one takes part. Bless the officers and teachers. Bless everbody thats our duty to pray for.

The next page lists grocery items: pineapple, coconut, oats, salt, soap, and fuses.

Beginning with her first diary in 1932, Mama Eliza recorded weather conditions: temperatures, drought, rain, wind, dust, lightning strikes, and thunderstorms. Forty years later, in her last entry, she wrote five words: temp 61 cloudy & cool. That day—May 24, 1973—she laid down her blue ink pen and diary for the last time. Five days later she died. With pencils and pens on 22 small notepads and diaries over 40 years, Mama Eliza wrote about a quarter million words and numbers.

Why did she write, and why so preoccupied with numbers? I don’t know,

but I’ve drawn some conclusions that may or may not be right.

The 843 sticks of tobacco in September 1934 looked like hope to Mama Eliza, a door flung open for her and the children to walk through during the long winter ahead without Granddaddy D. It meant cash until their spring garden came in. The 23 piglets from three sows was another door. They would provide meat in a few months. One or two would grow into sows or boars in the years to come. Several would be sold at the stockyard. Her numbers were about hope.

Numbers were her pile of rocks, too, her “twelve stones out of the midst of Jordan” (Joshua 4:5-11). Stones of remembrance of her awful misery when Granddaddy D died; a reminder she had not stopped and proof that she could and would go on. Numbers were a scotch between her and her fear of what was ahead.

Good numbers were also proof of the fruit of her hands and a cause for celebration of what was physically measurable: bushels of sweet potatoes, quarts of black walnuts, 12 new lambs, three dozen eggs, quarts of cream, pounds of butter. Mama Eliza was practical, not philosophical. She was a mother hen, turning her eggs to make them hatch. Many chicks meant good success.

Her figures were about gratitude as well. In her second handwritten prayer, she began with Heavenly Father We are so thankful… She had gone from empty to full. Her gratitude acknowledges her fullness was from the Lord.

On a Saturday, one week before Granddaddy D’s fall, Mama Eliza wrote that he bought seven pounds of fish to fry for supper. Later that night, he took his two oldest daughters frog gigging. The next day, they went to church. For 40 years she kept a record of her simple pains and pleasures. I’m so glad. They are a model for me: work, add up the numbers, keep account of good times and bad, and say with Mama Eliza, Heavenly Father, I am so thankful.

About the Writer: Brenda Evans is a freelance writer living on the edge of Appalachia in Ashland, Kentucky. You may contact her at beejayevans@windstream.net.

|

|