October-

November 2013

Journey of a Lifetime

------------------

|

The Little, Brown Box (Inspired by True Events)

by Noel Thomas Manning

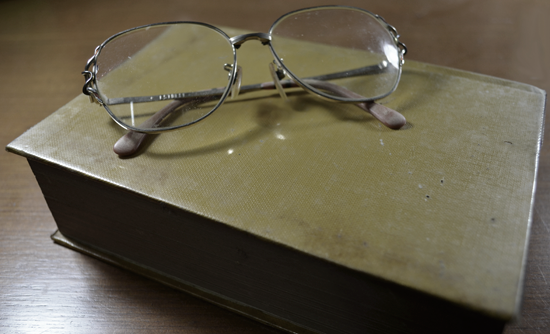

It sat at the corner of a side pew

for months. From my seat on the

organ, I peered toward it every Sunday

and wondered why no one claimed it.

It appeared to be made of wood and

in reasonably good repair—still

useful, though well worn. It was

a bit marred in places, scraped

and scarred, owing to its age

and handling, I imagined.

Every Sunday when I arrived at church, I expected it to be gone, but it remained in its place though apparently moved a bit for cleaning and dusting. I mentioned the object to the pastor, but he discounted it as not really important and stated that eventually someone would take it away. “After all,” he suggested, “it is not all that obtrusive.”

I wondered nevertheless why he or one of the deacons had not investigated it or at least inquired of the congregation, or why one of the cleaning persons had not discarded it (though I hated the thought). Why no one else was inquisitive, I did not know; but no one seemed interested or bothered by its presence, and some were probably neutral, perhaps oblivious to its being there. Maybe some had simply not noticed, but usually such out-of-place articles did not claim an unwarranted spot for long. Generally they were taken to the church office or assigned to a cluttered table with other castoffs, or to an adjoining room or closet.

I was curious but respectful. I still looked at it momentarily every Sunday from my vantage point at the organ. I thought it must have a story to tell, and after one evening service I could not restrain myself further. Something not mine had never before posed any real temptation. I did not know what to make of this feeling. I stood momentarily in front of the object, then lifted the lid and marveled at what I found inside: a leather volume imprinted with golden lettering with the symbols of a stained-glass window and a cross embossed upon its crimson cover.

I picked it up, held it for a long moment, then leafed through the volume reluctantly, almost tenderly—as though I were an unintentional intruder—wondering whose hands and eyes had stayed here and there on its pages, caressing it for untold hours—even days. I hoped that he or she would not mind my avid interest, my invasion of something not my own. The print was large. I reckoned this volume had belonged to an older person whose eyesight had dimmed or who wanted to read its truths easily without the aid of glasses.

I thought of a very tiny, elderly woman at my home church; I could envision her seated near the aisle, holding the Book on her lap while she gathered her shawl around her thin shoulders (like many of her era) against a real or imagined chill, but who believed every word of comfort, every promise, and “every chapter, every verse, every line,” as she had said.

I thought of an old man who always sat on the back row. Taking his pew early without fail, he sat quietly but was attentive to his surroundings, sometimes bending over his copy as if in prayer or solitary review. He would lift his head only when the minister made a strong point of exposition. Then he would intone a soft “Amen” and resume his posture. He had become a fixture.

I could see both of them in my mind although I certainly could not ascribe them ownership (except in a symbolic way). But I was glad that I had saved the memory of them and their reverence and of the sanctuary that had been so much a part of them, and of me. As I held the Book and remembered, I choked back some emotion as a tear fell. I quickly wiped it off from where my hand had guided me: Psalm 91. “He that dwelleth in the secret place of the Most High shall abide under the shadow of the Almighty.” My favorite assurance, it seemed a perfect place to have landed.

Scanning the thin sheets, I found many of the pages bent, a few torn, one or two soiled, and others wrinkled and faded but with still-legible print. I searched for a name—any handwriting that might provide a clue as to ownership, perhaps an address, or date. But I could find none; this seemed strange given the obvious value. I found only markings here and there and underscoring of favorite passages, highlighted words and phrases, and a few written-in remarks beside special verses. I fairly discerned the thoughts of one or several who here had planted their hopes.

The writing on various pages, in margins, and between columns reminded me of my late parents’ backward-slanted penmanship: carefully drawn in measured style as if to savor meaningful passages, but disinclined to mark them badly, as the treasure of this Book was inestimable and the truth herein eternal. On the inside back cover I could discern a block of twelve carefully printed capital letters: G I O R A S — A V P H I T. I would try to decipher their meaning later. G I O R A S — A V P H I T.

I handled the Book carefully, almost too carefully, and nearly dropped it as I tried to picture who last might have used it and had left it here, whether intentional or not. And replacing the volume to its resting place, I hoped (even prayed) that someone would claim it and continue to cherish it as before. Surely it had been important to someone, somewhere—perhaps a visitor to this church who, in haste or perhaps during conversation, had forgotten it. But why in a box?

“Love, sometimes, is not so easily seen,” my mother had once told me, “but it is always within reach.” I do not know why this thought came to me while pondering this little brown box and what it contained, except the whole story of it was love. The Book itself bore witness: it was well within reach, though not immediately obvious.

Several more months passed. The box remained, again to be moved slightly out of position by those who cleaned or sat on the pew. It continued to hold little if any interest for anyone. Once more I mentioned “it” to the pastor; he shook his head, shrugged his shoulders, smiled, and went his way with a parting remark: “Obviously no one wants it.” No one?

It was then that I decided to take it home. No one would miss it if I took it away; apparently no one cared or had considered it of any consequence. I did feel a tinge of reluctance and concern, for I did not want to take that which was not mine, but neither did I want to leave it abandoned, holding a thankless place even in this sanctuary of peace.

Was I wrong to take it? I asked the Lord. He did not answer except in that still small voice that assuaged my sense of guilt: the impression of His Spirit that had ministered so often before during my moments of indecision. I hoped I had not deprived another of its worth; I prayed that when I took it, the owner would know that someone cared enough to want it and would use it.

Although I own several Bibles, this is the one that now goes to church with me; this is the one I use when speaking from the pulpit, when teaching Sunday School, when studying, or when having daily devotions. This is the one I always use . . . feeling the spirit of those who have read it before and who, for whatever reason, had left it for another who would appreciate its worth. It fairly begged to be used.

Surely there were many others who could read its message and find whatever they needed: forgiveness and consolation, repentance or saving grace—a myriad of accommodations for the hungry spirit, a balm of healing for the broken heart and the sin-sick soul. Surely there were some who required this Book, who were bereft of scriptural admonitions and spiritual understandings. Perhaps for them this Book could have eternal meaning, but unless read, it would avail them naught. I had to believe that I had acted wisely, judiciously; I had to believe I had done the right thing, that I was justified in taking it.

One recent morning at church, while poring over the minister’s text for the day, my eyes settled upon 12 words that brought a proverbial chill to my spine: “God is our refuge and strength, a very present help in trouble.” G I O R A S A V P H I T: an appropriate injunction for the faithful.

Perhaps my supposed discernment was a stretch. Whether this was the intended meaning or not, the blocked letters on the inside of the back cover could now be related to an assertion of particular significance. It made sense to me; it certainly fit. I could not know, but for the former owner, maybe this was a reminder of that security that he or she had found, and on which he leaned.

I prayed the fervent prayer of seeking: searching for further enlightenment, although I felt secure in my faith. After many months of wondering, pondering, and what seems now like years of holding on to this Book, I have gained a new appreciation for the unclaimed blessings of Divine Providence. I well understand that others have a right to question my thoughts; they have a right to doubt the spiritual interchanges with which I dealt regarding something so simple as a little brown box and the Book it contained.

Others may be justified in relegating my reasoning to the workings of an imaginative and sentimental mind, the too-emotional musings of a senior Christian. And in truth, upon cursory notice (even with careful inspection), the little brown box and what it contained were nothing all that special. Considering the millions of Bibles printed and sold, read and unread, this Bible was just another Bible despite its unusual “packaging.” That is safe to assume—but since it is now a precious possession holding a valued status, I cannot help but wonder.

Although I am not one who subscribes blindly to “divine appointments,” I have nevertheless arrived at a simple but obvious conclusion. Somehow (and for a reason yet to be determined), this Bible must have been meant for me.

About the Writer: A graduate of East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, Tommy Manning is now a retired editor/writer, and has worked in Christian publishing for more than 50 years. For a short while he studied at Welch College in Nashville, Tennessee, and pursed further Bible studies in Atlanta, Georgia. A native of Ayden, North Carolina, he currently resides in San Antonio, Texas, where he is actively engaged in the music of the church, having served as a church organist from the time he was 16. |

|