April-May 2016

Outreach

Without Borders

------------------

|

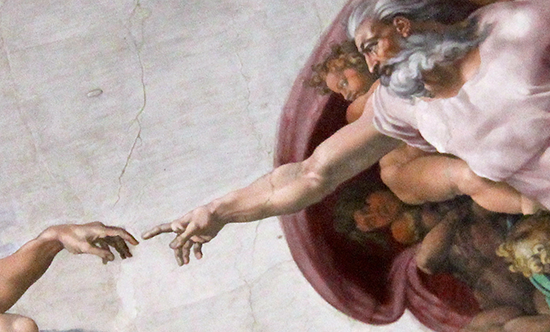

INTERSECT: The Image of God and Why It Matters, Part 1

In Genesis 1:26, God said, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness.” Verse 27 states He did so: “So God created man in His image.” This is said of no other creature in the creation account but is unique to humanity. So what does this mean, and why does it matter?

The image of God in man (sometimes called the imago Dei) has been a topic of interest to interpreters of Scripture for centuries, if not millennia. Over the history of interpretation, at least three basic ideas have developed about what this means. We will examine these views briefly, assess them, and draw out the significance the image of God holds for us today.

What Is the Image of God?

Some interpreters have emphasized that the image of God has to do with humankind’s essence or makeup. It is the essential aspect of what it means to be human. We might think of it in terms of man’s ability to think, feel, and act, as F. Leroy Forlines has often put it. Man is a thinking (mind), feeling (emotion), and doing (will) creature. These particular aspects of human life are in some way a reflection of the nature of God Himself. He thinks, feels, and acts, and He has made us to do the same.

Others have drawn attention to the fact that Genesis 1:27 says we were made as male and female. They stress the connection between the divine image and the potential for relationship. Man has the capacity to relate to God and fellow humans in a way unique from all other creatures. In fact, such a reality is essentially a reflection of the perfect communion experienced by the Godhead. The Father, Son, and Holy Spirit enjoy perfect and unbroken fellowship.

In more recent times, scholars have tried to define the imago Dei in terms of man’s function in the earth. Two main reasons are responsible for this interpretation. On one hand, Scripture seems to suggest a strong connection between the divine image and man’s responsibility to exercise dominion over creation. Some interpreters even go so far as to say God’s image and man’s prerogative to rule over the earth are one and the same. Others simply suggest that man has been created in God’s image for the purpose of serving as His representative on the earth.

Another aspect of this interpretation cites the ancient world as a parallel. This parallel is the relationship between ancient sovereigns and their vassals or political underlings. After conquering a city and its king, ancient superpowers often appointed their own ruler. These leaders, or vassals, represented the sovereign’s rule over the conquered land. Their authority was derived from the sovereign. This situation has been applied to God’s relationship with His own image bearers, who represent His rule upon the earth through devoted service.

So which view is correct? Each of these interpretations contributes to an understanding of the image of God in man. God created us distinctly so that, in some measure, we reflect His nature. This fact has to do with our very essence and is not simply a role we fill. Yet God has also created us as relational beings. We are not islands unto ourselves; we have been created to serve God in community, both with Him and others. It is equally important to maintain that God’s image enables us to fulfill the unique role He has given us to represent His rule over creation by subduing it to the Creator.

Why Is the Image of God Important?

Answering this question takes us back to the fundamental question of human purpose: why am I here? Or, what have I been created for?

God made humans for the sole purpose of representing His rule upon the earth. This role is not something we embrace after becoming Christians. Rather, we are made for this purpose. The entrance of sin into the world means this purpose has become twisted and distorted. The root of all sin is a desire to usurp our subservient role in the economy of God’s rule. We want to take His rule for ourselves. As the tower of Babel teaches us, we aim to make a name for ourselves, not for God (Genesis 11).

The story of redemption is therefore one of restoration and renewal. In one sense, it represents a movement forward toward our final salvation and deliverance from sin. But in another sense, it represents a movement backward as a return to Eden. That move backward, however, is to a superior reality where the possibility of sin no longer exists.

With this perspective in mind, how extensive is our responsibility as image bearers of the Creator? There is no limit to its extent. Forlines outlines four basic relationships that encompass the whole of human purpose: (1) our relationship with God, (2) our relationship with others, (3) our relationship with self, and (4) our relationship with creation. We often think about the first two, but not so much about the third and fourth. God’s plan is not so shortsighted, because it encompasses every aspect of these four relationships.

Redemption is God’s plan for renewing our ability to exercise the responsibilities associated with His image in us. As stated in Genesis 1:27, our role as image bearers is directly tied to the following command: “Be fruitful, multiply, fill the earth, and subdue it so that you might rule over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the sky and over every living thing that creeps on the earth.”

In the next issue, we will consider further the meaning of this command to subdue the earth. How can we do this in a fallen world? And how does this responsibility relate to the gospel?

About the Writer: Matthew McAffee is program coordinator of Theological Studies at Welch College. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree at Welch College, Master’s degrees from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and University of Chicago, and a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago.

|

|