August-

September 2014

Family: It Matters

------------------

|

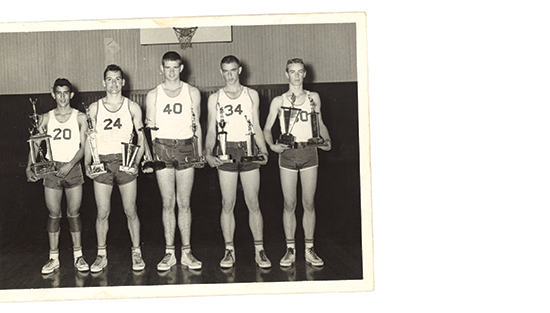

Photo: #20 James Rios; #24 Harold Kelly; #40 Larry Butler; #34 Mitchell Vining; #30 Mike Vining; #14 Jack Williams; #3 Raymond Mariche; #33 Henry Devoter; Coach Arlon Adams (sport coat).

Midnight on Butler Road

by Jack Williams

Larry Butler grew up on a West Carroll Parish cotton farm in northeast Louisiana. The 6’4” son of a Free Will Baptist deacon became a legendary basketball player at Forest High School and Northeast Louisiana State University, then coached basketball 36 years at Start High School in Richland Parish. “Larry the Legend” stepped into the fast lane of Louisiana basketball in the eighth grade when he started at center for both the Forest junior team and varsity. Opposing coaches faced five years with Larry as center at Forest.

I wish you could have known Larry Butler. He was more than a tall farm boy. He was intelligent, widely read, courteous, hard working, thoughtful, and a great teammate. Larry lived on the west end of Louisiana Parish Road 364, later named Butler Road. I grew up on another cotton farm on the east end of that same road. We rode the same school bus 11 years, which means it was unusual for the two of us to not see each other every day.

When Larry began playing, men’s basketball at Forest was mediocre at best. Two things changed that. Arlon Adams was hired as coach, and Larry Butler discovered a love for basketball. Arlon and Larry soon became lifelong friends. Arlon knew how to coach and how to communicate with farm boys. During Larry’s last four years as center at Forest, the team’s record was 26-14 (freshman year), 36-3 (sophomore year), 37-2 (junior year), 35-5 (senior year). He was named to numerous all-tournament teams, as well as All-State. Larry was difficult to guard. An excellent ball handler, he played defense with the tenacity of a Navy SEAL, could run four quarters without stopping, and rebounded tirelessly. Plus, he had a “secret weapon,” an almost unstoppable fade-a-way jump shot Coach Adams taught him.

He evaded clingy, man-to-man defenses, clearing the way for teammates to drive for uncontested layups. He infiltrated zone defenses with ease and scored with his patented fade-a-way jumper. He shot free throws well and consistently hit shots from 25 feet when needed. Larry was a player destined for more than high school hoops, and when he enrolled at Northeast College in Monroe, the entire Gulf States Conference soon understood why the lanky deacon’s son was constantly featured in local newspaper articles.

Band of Brothers

One element that made the Forest Bulldogs different during Larry’s years as center was the unusual composition of the squad, which included four sets of brothers: the Butler brothers, Larry and Robert; the Kelly brothers, Glen and Harold, both of whom were also All-State players; the Vining brothers, Mitchell and Mike; the Willams brothers, Jerry and Jack. The team almost had a fifth set of brothers, the Rios brothers, James and Raymond. James Rios was the fastest player in the state, with lightning quick hands. One of the Vining brothers, Mike, was later named to the Louisiana Sports Hall of Fame.

Larry Butler impacted many people during his years as a player and coach, one of whom was a young basketball player at Start High School who was struggling with his identity. His name was Tim McGraw, and he later became a world-famous country music singer.

McGraw said, “When I was growing up in Start, Louisiana, one of my greatest heroes was my basketball coach, Larry Butler. Not only was he a terrific coach, he made sure that we learned what it meant to be part of a team off the court, too. When it flooded—which it did every year—Coach Butler would load up his players in the back of his truck and take us to the local cotton gin where there was a huge pile of sand. We would fill sand bags, load them in the truck, and bring them to people’s yards and anywhere else they might be needed. It was Coach Butler’s way of teaching us how to give back to our community, a premise that is central to The Neighbor’s Keeper Fund.”

The fund is a charitable organization Faith and Tim McGraw founded in 2004 to help people in need and to encourage the spirit of neighbors helping neighbors. To further demonstrate his love and respect for Coach Butler, McGraw also established the Larry Butler Memorial Scholarship at the University of Louisiana at Monroe. The scholarship is for men’s basketball.

Midnight on Butler Road

During basketball season, each week began for the players with a three-hour practice Monday night. We would run 40 laps on the gymnasium bleachers, followed by push-ups, position shooting, and wind sprints. Larry often ran beside me. His shoes were ragged from hard use. The pace never slowed. Game nights were typically Tuesday and Thursday, and weekend tournaments usually included three or more games. When the team played “away” games, we usually rode in cars or on a school bus, arriving back at Forest between nine and eleven o’clock.

Since few of us had vehicles, we’d walk five miles home—in the dark, on dirt or gravel roads until midnight. If it rained, we walked wet. If temperatures dropped, we walked cold. The four of us (Larry and Robert Butler, my brother Jerry and I) logged many miles walking home after games. Dogs growled and barked at us; vehicles passed with a honk or wave while we walked home as quickly as possible. Midnight on Butler Road was lonely, dark, and sometimes scary.

Teen Pastor

I became a Christian at age 16 and was called to preach eight months later. I well remember the first Sunday School class I attended at Sardis Free Will Baptist Church on the west end of Butler Road. The teacher wore blue jeans, ragged tennis shoes, and a sweatshirt. He was also my friend. He pulled a folded quarterly from his back pocket and talked for an hour. Larry Butler kept my attention that day. He was a good teacher—well prepared, interesting, and practical.

The Sardis Church voted me in as pastor in 1959. I was 17 and a high school senior. I was an awful pastor, but the congregation loved me anyway. One Sunday morning when I gave the invitation at the close of my sermon, Robert Butler came to the altar and was saved. He was my first convert and eventually became a preacher also.

When church leadership suggested that I begin visiting in the community and invite people to church, I was terrified. But Larry Butler volunteered to accompany me on the door-knocking adventure. We walked from house to house knocking on doors, making friends with neighborhood dogs, and inviting folks to church. Since I had a stuttering problem, I had to repeat myself often, but Larry never wavered.

He kept the dogs at bay and introduced me as his pastor. I was embarrassed for him. That was the day I knew I loved that tall deacon’s son. When the door-knocking vigil finally ended, I walked home, turned on the radio, and listened to the Grand Ole Opry on WSM, a longtime family tradition…and worked on the Sunday morning sermon.

Different Paths

My time with Larry Butler ended sooner than I expected or wanted. After I finished high school in 1960, I moved to south Arkansas and worked as a lumber grader in an oak flooring mill, then relocated to Nashville to attend Welch College. The last time I saw Larry play basketball was in the fall of 1960, his senior year. He and his Forest teammates won that one also. Our paths drifted apart as ministry responsibilities took me to California until 1977 before returning to Tennessee.

Larry was also busy as a coach and educator for 36 years. His Start High School teams were incredibly successful, earning him a career record of 546-235. He also taught history and served as principal, until his influence came to a sudden and tragic end.

He suffered a heart attack during a basketball game in Cleveland, Mississippi, on January 18, 2002, and died at a hospital later that day. He was 58. His brother Robert officiated the funeral. Two of the pallbearers were former teammates at Forest—Harold Kelly and Mike Vining.

It’s midnight again on Butler Road. Oh, how I wish I could walk that dusty road with the tall deacon’s son and watch him shoot the fade-a-way jump shot one more time. But it is not to be, because Larry Butler has answered a higher call. He finished his course; his tennis shoes are no longer ragged. The boy from the Louisiana cotton field continues to cast a long shadow and impact people for good. Just ask Tim McGraw.

About the Writer: Jack Williams is director of communications at Welch College. Visit www.welch.edu for more information.

|

|