June-July 2020

Heart of the Storm

------------------

|

Dear Sir & Son

By Bill and Brenda Evans

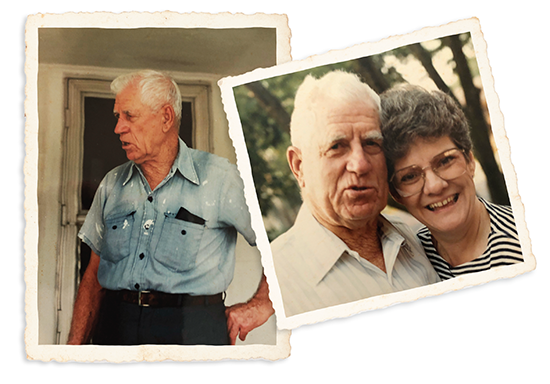

William Lee Evans wrote first-rate letters. We have a hundred of them, written between 1980 and his death in 2008. We kept them because he was Dad, and in his letters, we see his face, hear his voice, and hold onto the man we lost.

Jan. 11/06

Spgfld, MO

Dear Sir & Son

I found a Nother Nickle so I thought I would Send it on While the Intrest is above

10%. You know Us po folks Need all We can get. I hope Your Florida trip went Well.

As you can see I Cant rite. My arm is Stiff and I need an excuse so I guess thats as good as any.

Well We finally got a little rain. I think about .8” & three Flakes of snow. Weather Man thinks We might get a bit more rain. First of next week I hope.

I’ll go for now don’t want to tell All I know in one letter. I love you,

Dad

The “Sir” in Dad’s salutation was his humorous acknowledgement that I (Bill) was then-director of Free Will Baptist Foundation. Of course, his “nickle” was more than five cents. I don’t remember how much, but enough to create a new gift annuity. He already had several gift annuities with Free Will Baptist Foundation and knew interest would be high because he was almost 88. Dad liked good interest on his “nickle,” and he was a giver. His two goals were getting good interest payments as long as he lived and giving to our denominational work when he died. A gift annuity would do both.

Dad was born in 1918, in Hazen, Arkansas. His mother, 22-year-old Claudie Lee Barnes Evans, died a week after he was born. She was the second wife of 47-year-old William Thomas Evans, whose first wife died after birthing seven children. Eventually, William Thomas Evans married a third wife and had nine more children, a total of 17. Dad was the eighth and only child by Claudie Lee.

Dad was raised by his maternal grandparents, Pa Barnes and his wife Margaret, who moved from Arkansas to Vernon, Alabama. He remembered seeing his birth father only once. After eighth grade, Dad quit school and hired out raising turkeys and doing general farm work for a neighbor. He loved ham and other hog meat but had no respect for turkeys. “Dumbest animal in the world,” he said. “You had to kick them to make them move, or they’d smother each other.”

At 18, he married 17-year-old Braxine McDaniel. A year later, Margaret was born, and two years after that, I came along in a two-room sharecropper’s house on the Hunter Young farm near Vernon. Soon after, Dad went into sawmill work at Lumber City, Georgia, and Gatman, Mississippi.

I remember Gatman. We rented a two-room shotgun house a few feet from a railroad track. It was rough-sawn

board-and-batten on a two by four frame. It shivered and shook but didn’t fall down from the rumble and clatter of trains. One-inch boards were both the inside and outside walls—unpainted, of course. Somebody said modern board-and-batten houses “exude a comfortable informality.” In Gatman, we didn’t talk much about comfort or informality. We were committed to being neighborly, loving, laughing, and getting by.

When Dad got a job with the Frisco Railroad as a welder’s helper, we moved back to Alabama (Sulligent this time, on the Buttahatchee River) and rented four rooms off a central hall from Aunt Marthie-Ann (no relation) who had four rooms on the other side of the hall. A well was close out back and an outhouse over a steep hill.

Dad’s job with Frisco was with a maintenance-of-way gang. He worked ten-hour days, seven days a week for four or five weeks in a row. He lived with the gang in a box car converted into a bunk car, and then came home for seven or eight days. On the gang, he earned a little extra money as “crumb boss”—sweeping the camp car where the crew cooked and ate. His favorite job was operating D4 and D7 Caterpillars. But when Dad came home, we worked the garden, split stove wood, made house repairs, and walked a mile to church. About dark every day, he was all ours in the front porch swing.

Margaret on one side, me on the other: pumping the swing, laughing, telling stories, and fighting Buttahatchee mosquitoes.

In 1948, Dad was promoted to maintenance-of-way

mechanic, and Frisco made us move to Springfield, Missouri. He stayed on the road for another 30 years, in and out of cheap motels and greasy-spoon restaurants, home only on weekends and holidays until he retired early

to care for Mom whose health was really bad.

Soon after retirement, Dad began to write us letters. Phone calls were paid by the minute back then, and Dad was never one to spend when he didn’t have to. I was traveling a lot with my job, so I called, but Dad wrote. We are so glad he did.

In June of 1989, Dad sent me (Brenda) a letter. He had always called me Jane, my middle name—the only person who ever did—and I loved it. But in this letter, he didn’t. I don’t know why. We lived in California then. I was teaching and had just completed my M.A. in English. In late June, we would head to Kentucky for our son Lee’s wedding on July 1. On our way east, we planned to stop in Springfield to see Dad.

Springfield, MO.

June 3, 89

Dearest Brenda

I guess You Are Well rested With Nuthing to do With All thats going on. As the Monkey said when he got his tail in the Lon More (It Won’t be Long Now). School is Nearly over and No 2 Son is Almost Married. Makes a feller Wonder how Much all this good Stuff a feller Can take. Your Graduation in amongst all that I’m sure Was not light. You’ve had a Pretty full Spring thus far. I kindly hope things Will slow up just a bit for you all After July 1. When you get as old and no good as I am things Won’t bother you Much Unless you have a Straw Patch [strawberry patch]. Then You’ll loose your Mind for a few weeks. I’ve had at least 50 gal. I’ve given 25 gal Away and Put Berries Away until the World looks level & I still have a few but I’m Not fixing anymore I don’t think.

I’ll be looking for you Western People About June 25th before you go on to KY. Congratulations on You Schooling. I’m Proud of You, and Still glad you are ours & think We’ll just keep you. I Love you Verry Much.

Dad E.

Dad’s letters were a one-sided conversation and often funny. They are models for the art of personal letter-writing, although he would have laughed at the idea that they were a model of anything, much less writing. Anyway, here’s a bit of advice he’d never give you.

Go ahead and write and do it like Dad—in your voice, like you speak. Be ordinary. Worry little about spelling and punctuation. Add dates and places. Cause us to mull, smile, remember. Be serious, too, but also random. Joke; be self-deprecating. Of course, be yourself and say what’s going on. Dad knew I was worn out, and he was worn out, too, from his strawberries. So, when he says, “I’m Not fixing anymore I don’t think,” we know he will. We knew Dad. He would not let plump berries rot on the vine. And he knew that we knew.

But you say, “I don’t write personal letters anymore.” You email or text or tweet, don’t you—or post on Facebook? Learn from Dad. Do it in your own words, show your face, the gleam in your eye. Bare your grin and zigzagged wrinkles. Let readers hear your voice, feel your soul. Let them taste your strawberries.

About the writers: Bill and Brenda Evans enjoy being “young-old” and retired because they like books, Sudoku, jigsaw puzzles, food, more books, travel, and volunteering in Ashland, Kentucky.

|

|