A Day Watered With Blood

By Brenda Evans

“Darker and darker are the clouds which gather around Israel”—so begins Alfred Edersheim’s re-telling of the Battle of Taanach by the waters of Megiddo where Sisera’s 900 chariots of iron rumbled out against Israel’s ill-equipped foot soldiers—thunderous beats of Sisera’s steeds, clatters of steel wheels, maniacal shouts of enumerable troops. The sounds of Sisera must have terrified Barak and his 10,000 inexperienced Israelites waiting on Mount Tabor. Plus, there were the optics—swift stallions hitched to armored war machines and foot soldiers, well-weaponed in battle regalia.

Despite all that, Barak marched down Tabor and into the valley with the 10,000 at his heels (Judges 5:15). From the heavens came the Lord’s “direct interference”—heavy rains, Edersheim says. The armies fought. From their courses in the celestial sphere, stars also fought against Sisera, Deborah sings in her victory song (5:20). All God’s universe came down on Sisera. Horses slowed by wheels bogged deep into the sog. Barak and the 10,000 pursued. Chaos followed and “the host of Sisera fell upon the edge of the sword.” The ancient torrent “Kishon swept them away” (5:21). Baal, the main god of the Canaanites and the god of storms and weather, was thwarted by Israel’s “God of the gods.” On foot, Sisera fled to the tent of Jael, a wild and weird bedouin woman. By age 30, according to Jewish tradition, Sisera had conquered the whole world. There was not a place the walls of which did not fall before his voice. That’s a bit of Jewish hyperbole, undoubtedly, but more factually, the Scripture records Sisera oppressed the people of Israel cruelly for 20 years, with the backing of Jabin, king of Canaan (Judges 4:3). Yet on this day and on foot, Sisera fled—straight to a nomadic tent, Jael’s fatal House of Hair.

Why did he flee to Jael, the agile mountain goat, as her name implies? I don’t know. I understand why Sisera ran from Barak (lightning) and Deborah (the bee), but why to Jael? Or better said, why not? He knew Heber the Kenite, Jael’s husband, because there was peace between Jabin the king of Hazor and Heber the Kenite (4:17). Perhaps Heber’s tents were near and Sisera knew it. Add to that, the law of hospitality was strong among desert peoples. If a fugitive—even a fugitive from blood revenge—could reach a nomad’s tent or even “touch the ropes of it,” he was safe for two days and the night between, according to John Paterson in The Praises of Israel.

Still, there’s the question: why Jael’s tent, rather than Heber’s? We can speculate. Maybe Heber’s tent was empty because he was away. Or Jael’s was the first Sisera came to. Or he knew Jael well and anticipated more kindness from her than from Heber. Or he hoped for safety or even sexual favors from this tent-dwelling, wild and weird Kenite. How can we know?

But we do know the rest of the story, so we follow Sisera into Jael’s tent. We want to watch, then we don’t want to watch. Something bloody and unimaginable will happen past Jael’s tent flaps.

Sisera asks for water. Jael brings him milk from her sheep or goats, also clotted milk or curds or cheese or butter. We don’t know which. The Hebrew hem’a can mean any of these dairy items. In any case, the food is special, already prepared by Jael for Heber, their children, a friend. Perhaps soured or shaken in skins to form soft clots or heated that very day to form curds. The bowl is beautifully decorated, lordly, fit for a noble, which Sisera seems to be, though his garments are those of a military commander’s, disheveled and sweaty. He is dark, handsome, muscular, arrogant, I imagine. His sword still swings from his left side. His chariot is missing, washed away, along with his slaughtered or drowned army back at the battlefield.

Inside Jael’s black goat-hair tent, the cinematic scene scrolls on. This agile, wild, and weird mountain goat covers him with skins or woven blankets. He is drowsy and commands, “Stand at the opening of the tent, and if any man comes and asks you, ‘Is anyone here?’ say, ‘No.’”

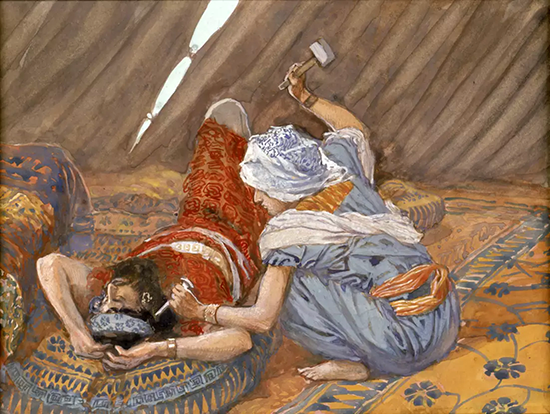

She nods. He snores. Jael eases out the tent flap, pulls a peg from its anchoring place, takes a mallet in her right hand, and goes to him softly.

The death scene is dramatic. Jael raises the mallet and strikes the peg through Sisera’s temple until the peg goes down, down into the ground. The blows crushed his head, shattered and pierced his temple. He lay dead at her feet (5:26-27). The audio is loud—wham, wham, wham of the mallet. The video is blood-spattering, crushing, violent beyond words. We step away, not wanting to hear or see more.

I understand Sisera. He was the relentless warrior and well-armed enemy of God’s people who lived in Canaan. Now he is dead. Good and dead, no question. As for Jael, she is a puzzle. She knows God’s people, the Israelites, but her husband is a friend, we assume, of Jabin and Sisera. Is Jael? Her husband is a Kenite. Is she? Her husband has made peace with Jabin and Sisera. Did she?

All we know for certain about Jael is that she was a tent-dwelling woman who became an assassin. Some Bible commentators straddle the fence about this wild and weird woman. Yes, she killed Israel’s enemy. That is good. But no, she’s not a woman of God, nor did she do a godly deed. Others say she was a good instrument in the Lord’s hand, as Cyrus was in the book of Daniel.

I’m baffled. There’s so much ambiguity here. I do know this. Jael was a pretender. Some would call her a shadow warrior, as the espionage novelist Tom Clancy defined shadow warrior—a special force who uses subversion, does what is not expected or even legal, including execution, for a greater good. Her duplicity is obvious. “‘Turn in, my lord, turn in to me; fear not,’” she said. (4:18). She sheltered Sisera, fed him, covered him, and killed him.

Was Jael justified? Commentators are all over the place. Some say her deed cannot be acquitted of the sins of lying, treachery, and assassination. Others say Jael did a good thing; God no doubt ordered it. Still, that does not justify Jael. It was a flesh and blood deed, a Kenite deed, not of God and His word. But Sisera was God’s enemy; she had to kill him. One commentator declines to say yes or no because, he says, “the Scripture responds with solemn silence” regarding whether her deed was good or bad. So, I remain baffled.

For the most part, the book of Judges is a dark time filled with tragic stories. Even grand military victories like Samson’s and Gideon’s are tainted with spiritual defeat. The final words of Judges sum it up: “Every man did that which was right in his own eyes” (21:25). Yet, God’s purposes went forward despite the leaders’ flaws, failures, and outright sin. That’s how I take the Jael event. As Deborah told Barak before the battle, God’s purpose was to “sell Sisera into the hand of a woman” (4:9). And He did.

What is the take-away for me as I commit to pursuing God’s purposes in my life? First, like Barak, will I refuse to stand or go without a human crutch on lean on? Second, will my history show I am one who rises above when the “zero hour” bears down on me—or that I fell below? Finally, will I admit my thoughts are not God’s thoughts, nor my ways His ways (Isaiah 55:8)? Like it or not, I am a soldier in life’s battles—battles that will test my faith, my grit, my courage to carry on. Will I pass or fail the test?

About the Author: Brenda Evans lives and writes in Ashland, KY. You may contact her at beejayevans@windstream.net.

Photo: Wikimedia commons. Public domain. Jael Smote Sisera, and Slew Him, circa 1896-1902, by James Jacques Joseph Tissot (French, 1836-1902) or follower, gouache on board at the Jewish Museum, New York.

|